My journey to the ‘sweet little cabin in the woods’ started well, I took Campanula incurva as a good omen.

The road up into the hills leaves the coast here. Agamemnon is advertised. I was about to leave my guides behind, the books and websites which had taken me up into Mount Olympus, up through the gorge at the front of the mountain from Litochoro, and had led me to Papa Rema, told me where to find Jankaea heldreichii, given me the name of the lovely white saxifrage, Saxifraga scardica, which covers the rocks on the way up to the first refuge, pinpointed the spot where the little dragon grows, and had taken me eastwards to Falakro and Pangeo and listed most of the plants I had discovered on the heights of those mountains, and now I was on my own, and after driving back on the motorway from Thessaloniki I was about to leave the noise and the signposts and the graffiti and the tired beaches of the coastal strip and strike out on my own.

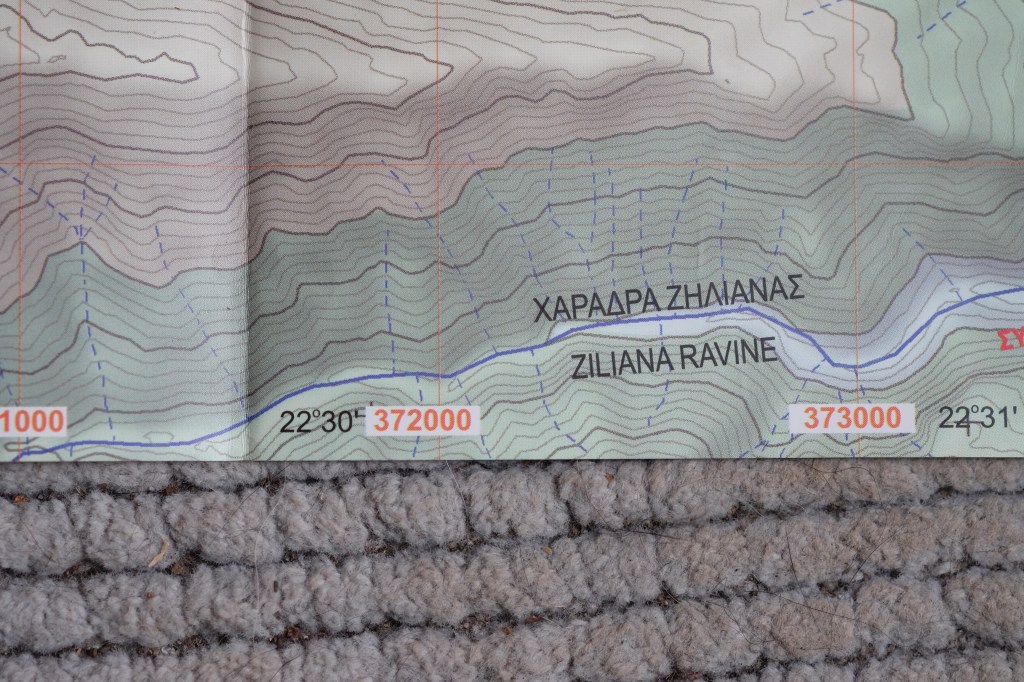

But I was off the map. Off the detailed map, what we call ordnance survey maps.

I was heading for the edge of the carpet. I did have two road maps which gave me these images:

The top map does at least show Ano Skotina. I was on the road from Neos Pandelemonas – you can just see a chess piece style castle – which winds up and up through beautiful woods of sweet chestnut. I had assured my hosts in a text message that I could get to Ano Skotina and they had told me to look for a blue sign and a kiosk showing where the steps down to the house left the road.

Of course I also had google maps, which gave me this:

Or this:

Sintrivanis Mountain is not a mountain, but a place to stay. At the time on the google map there were one or two more details, including a purple tear drop which led me on like one of those lights the cornish wreckers are said to have placed on dangerous clifftops to lure sailors to their doom. I still don’t know why I was unable to find my way into the village; I became too angry with myself and with google and the map makers to understand what I was doing, so that I can’t explain how I became lost. At village level google maps don’t distinguish between what John Richards calls sealed roads and stony deeply rutted or treacherously sandy tracks. In the end I followed a half sealed road which became a steeply descending sandy track so I stopped the car, by that time I hated it anyway, and carried on on foot towards the purple tear drop. Through the trees I saw a building a hundred yards away. It had an empty, abandoned air but there was nowhere else for me to go. Almost certain that it was wrong but compelled to get to the end of my foolishness I set off through the bracken, angrily. The nearer I got to it the clearer it became that it was a ruin, with no sign of any recent human activity. I walked back up to the little red car feeling sorry for myself and met three people out for a sedate, late-middle aged stroll. Their slow evening pace was a rebuke to the foolish foreigner trapped in his car, an intrusion in the forest. I envied their ease and resented the way they seemed at home, at home with nature, putting the finishing touches to a good day. Of course they would have driven up and would be staying in the hotel in the hidden village. But they had now put their car behind them and whatever worries and responsibilities they might have carried with them from the city. They picked wild strawberries from the bank and offered some to me to prove their intimacy with the forest, with the golden evening, with nature. One of them spoke French, as elderly europeans often do. French was my last card. I tried to explain my problems, like there being a phone number in a message that I could try to ring, but that I couldn’t remember the phone number long enough to dial it, especially in my agitated state, and I didn’t have a pen. They were very helpful in the way a probation officer might be to a chaotic delinquent. I knew I had spoiled the peace of the evening. I knew that precious time was slipping away. I wanted to say, this idiot is not me! I am a walker, unhurried through long days out on the mountain and in the woods, hearing bird song, naming rocks and flowers, curious about farms and gardens, greeting other walkers and sometimes helping them out with a bit of map reading or identifying a plant: as the guide from Litochoro said, I’m one of those who loves the mountains best! Striking out on my own …. No, I was just an idiot – how could I not know the way to Ano Skotina, we were almost there.

Between us we memorised the phone number I’d been given and I got through! A kind voice said the best thing would be if I went into the village and met them by the church, and then they would guide me to the house. The French speaker said they would show me the way to the village. So they continued at their proudly relaxed pace and I drove, hating the car. I would drive a few yards as slowly as I could, but not slowly enough, because I kept getting ahead of them, so then I would stop and wait, get out of the car, look at the trees, drive a little further… In the end he took pity on me and got into the car with me and we drove the short distance into Ano Skotina, with him telling me every now and again to be careful of the road, since he’d decided I was not to be trusted. We met Yiota and her daughter or was it Yiota and her mother in the centre of the village and they were very sweet. But I shouldn’t have driven all the way in because then I had to reverse between two tight stone walls to get out again, back up the way we’d just come and lo and behold, the blue sign turned out to be the faded sign announcing Ano Skotinawhich we’d and the kiosk was as given in definition number 2 in the Oxford Dictionary: kiosk 1625. [Turk. kiushk pavilion, Pers. kuskh palace, portico.] 1. A light open pavilion or summerhouse, often supported by pillars; common in Turkey and Persia. 2. A light structure resembling this, for the sale of newspapers, a bandstand, etc. 1865. I assume they had given me a translation into English of the famous greek περίπτερο, (periptero,) pavilion, lodge, summer-house, kiosk, which anybody who’s ever been to Greece will recognise and which featured in our city lit Greek classes, threatened now by the ubiquitous mini-market: like a little covered stall selling soft drinks, sweets, bus tickets, bottles of water etc. But this kiosk was the bare minimum, just four posts and a little tin roof.

Parts of this story are illustrated in ‘I cried to dream again’, (Caliban in the Tempest): post cards from Olympos

There were seventy two steps (one for each year of my age) down to the house which was lovely, all the lovelier for arriving there. And they’d left me wine, fruit, cakes and I don’t now what else. And I arrived just in time to see the sunset over the Aegean, down across the forest, miles away.

But I didn’t! I’m still hopelessly confused! The house faces east, the coast of Macedonia faces east! That’s the sunrise, not the sunset. How can I be so ignorant of a place I feel I know so well. Anyway, although I didn’t see the sun go down, but I did see darkness deepen the sea, and distant lights begin to twinkle, and stars appear. (When you see a photo like that do you assume it’s sunset? Because we’re more accustomed to looking at the sunset, specially on holiday with a glass of wine on the terrace, because we’re usually still in bed when the sun rises in early June?)

In this house I felt alone for the first time. It was a place to share, a place to sit and drink, to watch the clouds, to follow the tortoise. Maybe it’s because I was on my own that I hardly stayed still.

There are pictures taken around Ano Skotina in the back of Olympos including this sunrise. I’m confused too, which is not surprising. But I’m trying to hold tight and not wander too far.

I’ve just started to read Landscape and Images by John Stilgoe – the chapter Walking Seer is about Thomas Cole the painter as a walker, (in New England in the early 19th century) and the perspective that gave him. Exposed to storms, unhurried. Thoreau too. Sundown light, acute-angle sunlight, maybe through a narrow strip of clear sky low on the horizon, becomes part of the destination. Cole is compared with his contemporary traveller, Timothy Dwight, President of Yale, who journeyed on horseback and published his four volume Travels in New England and New York in 1822. Stilgoe finds him hurried, always he has an eye on the inn at the end of the day. He can escape the storms which Cole observes and experiences intimately. He sticks to the turnpike roads, Cole was free to leave them. The horse holds him high above the perspective of the walker. He would be high above the strawberries, or if he saw them and wanted to taste them he would have to dismount.

Vividly I remember squeezing under a rocky overhang in a forest in Slovenia to escape a storm. It was good just to lie there. Eventually the rain began to drip through onto my head and demonstrate the famous cave forming porosity of the limestone. Adversity and exposure to storms or to heat and drought act like a kiln to fire and harden memories.

Vivid also is crouching beneath a crag in the upper Kiental in Switzerland one very wet afternoon, soon I was veiled by a thin waterfall through which I saw some way off a woman descend gracefully the steep path from the Gspaltenhornhutte with two small children skipping through the downpour before her.

Thoreau of course was the great wilderness apostle, and for him walking was a calling. He was a knight of a new, “or rather an old, order – not Equestrians or Chevaliers, not Ritters or riders, but Walkers, a still more ancient and honorable class, I trust.” Those Swiss children were new members of the old order of Walkers, truly Elect because they didn’t know they were.

But it occurs to me, not that I know anything about horse riding, isn’t the rider free to look around, like a passenger on a train? In westerns the man on horseback scans the horizon, is always watchful, unless half dead of course, when he can slump over the animal’s mane and be slowly carried to safety. Whereas the walker has to watch her step, and the driver has to keep her eye on the road. Especially in rough mountains I have often found that I have to stop in order to look at my surroundings because I have to be always thinking exactly where to put my feet. Attention to scenery has brought about many a sprained ankle. And if tired and carrying a rucksack, even on a level track, the walker’s head is bowed. On the other hand of course, you then become aware of all the small plants that grow close to the path.

In July 1835, Cole set out on foot through the New York mountains, starting at nine o’clock at night and heading for an inn. He grew thirsty, and not wanting to awaken any homeowners in the dark houses he passed, he pressed on through Rip Van Winkle’s Hollow. Finally, extremely parched, he found a brook. “There was a tin vessel glittering by the rill, placed there for the use of travellers, by some generous soul, perhaps fairy, that expected us at that silent hour.”

A different kind of walking, from the same period: in 1819, already with TB, Keats sometimes walked from Hampstead to Walthamstow, where his sister lived, (about ten miles?) because of course there was no public transport and he couldn’t afford a carriage.

Stilgoe connects Cole’s probably fanciful ideas about fairies with his English upbringing – he migrated to America when he was eighteen. Maybe he didn’t know that the native fairies had been banished from New England along with the native people. The Walker is a member of the Elect, a chosen one, blessed through courage and suffering with visionary insight. Nowadays, if you’re in the right mood and alone or with the right companions, you can park the car and once again join Thoreau’s Elect, if only for an evening.

I remembered walking in zig zags on and on up and up through a forest in Slovenia, also in July, dry, limestone country, and although I had water with me – I always take a plastic bottle and for a fortnight I use a bottle designed for a single use, Morrison’s 1 litre juice bottles are good, as good at the end of a holiday as at the beginning – I probably didn’t have enough and naturally I’m not tough like pioneers in New England, so I was pleased to come across a little piece of plastic pipe one end of which had been inserted into a very small spring from which water leached gradually into bright moss beside the path. Somehow the pipe skimmed clean water from the spring and it flowed gently above the swamp and trickled nicely out at the other end, making drinking easy. I didn’t think of fairies, but I did feel grateful to some generous, ingenious soul.

And my nephew, who as a very young man walked from Mexico to Canada along the Pacific Crest Trail – the trick is to leave the first mountains as early as you can, as the snow melts, and to arrive at the last mountains as early as you can, before it falls again. He left Mexico in May, I think, and snow began to fall in Canada on his last day, in October – so there’s snow at each end and in between it gets very dry and very hot, and he told me this story, that at certain places along the way, in the hottest driest places, where a desolate east-west road might cross the trail, you will come across stashes of water bottles, left there regularly by local people. I wondered what kind of people they would be, and my ignorant mind played with American stereotypes. Would they be kindly fascists? Would they be wholesome eco-freaks? Unemployed cowboys? Genii loci, the spirits of the place. When we are at our wits end, exhausted, lost, childish, foolish and becoming with each moment aware of our folly, no longer sure of anything, unable to remember our own phone number, then any vision or happening or meeting takes on an other-worldly quality. Other worldly comes naturally to mind when security and familiarity have been stripped away. Good fairies or their works then appear. Like emergency doctors. The person who brakes and stops decisively when you were stuck hitching for hours. Or the bad fairies who get you lost and damage your kit and eat your last piece of chocolate. These magic moments can only occur if you take risks and become vulnerable, or at least, as they say, go beyond your comfort zone. And when you go beyond the limits of self-reliance, and become dependent. The good fairy doesn’t judge you. Well, they shouldn’t. I thought that the fairies of Ano Skotina did, although I could have imagined that. After they had rescued me I never saw them again, in fact I never saw anybody in Ano Skotina. I visited the village and marvelled at the church and the great plane tree at six o’clock in the morning; the place was silent, asleep.